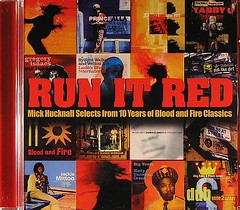

Blood and Fire, really and truly the best reggae reissue label in the world, turns 10 years old this year. To commemorate this momentous and wonderfully happy occasion, they've issued this terrific, King Tubby-heavy collection of tunes. You can check my review in the Montreal Mirror, and, in commemoration of this event, I thought I might as well dig an interview I did with Steve Barrow-one of the nicest fellows around. He and his family make sure I'm fed well whenever I'm in London. Anyhow, this was a great conversation and it's so much longer than what I'm going to post here. If you want the rest, just ask and I'll take the time to edit it enough so it's presentable-there's lots more good stuff-Steve talking about kids who listen to loud car stereos, how to pick the best punanny version, and the fact that he's not the biggest fan of Lee Perry. I'm a little low on time at the moment. Oh, and if you're interested in the Tree of Satta we're talking about and you don't already own it, run, don't walk. Seriously. It's wicked.

Originally published in Under Pressure magazine, August 2005.

Something sensible in the dance

One of the founders of renowned reggae label Blood and Fire, Sterve Barrow’s been behind the reissue of masterpieces like the Lee Perry-produced Heart of the

E: Do you think that today’s Jamaican music will last?

S: That’s a good question. Will people be playing Elephant Man in 20 years? Yeah, I think there will be a couple of tracks. There will be odd albums, tracks by Capleton, there will be the Black Woman and Child album from Sizzla, there will be the Real Revolutionary album from Anthony B—those albums are classic albums in any period and as good as anything from the 70s and better than a lot of the crap that was put out in the 70s that people don’t remember now. Will there be people collecting these records in 30 years time? I bet they fucking will. If people collect Smiths records, the worst deejay in

There are classic records being made like Luciano, and Jah

E: A lot of the glorification of the 70s results from believing what was around back then was fantastic, but there’s been years to sift through it. We just need to give time for 80s and 90s reggae to sink in . . . we need to figure out how to listen to it. I’ve often thought that in order to appreciate this you need to appreciate the context. To understand the Sleng Teng, stand in front of a sound system playing it.

S: Yes. When you play it on a casio keyboard using some little preset, it’s sort of a take off of Eddie Cochrane more than anything else—some rock rhythm programmed. When you play it through a big sound like Jammy’s, it’s going to sound like a killer.

E: What led you to release Tree of Satta with the range of artists you chose?

S: I know that it’s a classic riddim. Having played the riddim track for the last 6 years—and I’ve had various people deejaying and singing on it—it’s an inspiring riddim. Everyone knows the song, it’s a standard. When Bernard Collins came to us with the project, he only had 14 cuts, so I said what about getting some new guys on it? Anthony B was my first choice and he’s someone that’s always impressed me out of the new artists. He’s better than a load of people from the 70s. Way better. It’s because he’s got more to say.

I had no idea he was going to record Natural Black and, sure he’s got a little bit of Buju in the deejay part, but he’s got a great hook on it. It was also good to get someone from the 80s like Tony Tuff. Bernard, I knew, would instinctively get good performances.

E: The Capleton track is absolutely incredible.

S: The Capleton is brilliant. “Dislocate” is real revolutionary lyrics except that what he’s offering as an alternative leadership is not, to me, going to take people very far on the road they need to go on, but then again, no form of idealism is going to take people very far these days. It’s going to be undermined and eroded by reality. If anything, Capleton corresponds to the zeitgeist. He’s a little more hysterical. And that reflects society. Society’s going hysterical. It’s just part of the craziness of the world.

E: And these musical forms enable people to discuss this stuff—to discuss society and other things that might not be possible otherwise. Shit like sexuality, politics, culture . . .

S: Exactly. That’s it. These artists raise an agenda that is totally excluded by modern social democracy. Modern social democracy says you can vote, you can have an opinion on these things once every four or five years, then the rest of the time, “Fuck off! We’re not interested. You want to protest, go ahead, we don’t give a fuck.”

E: If you are so convinced of the 70s as the best time in Jamaican music, it also means you are more interested in the music than the agenda that’s being raised—because if you are interested in what’s happening in a nation like Jamaica, then you’ve gotta be interested in stuff that people are saying now, 5 years ago, 10 years ago, any time since the 70s.

S: Yes. Some of the people I sell records to thought that by having Capleton on a Blood and Fire release it was a big betrayal. But if I want to put Capleton on a classic riddim via Bernard’s production ability, I’m going to do it, because I like Capleton. When I played “Dislocate” to Bunny Lee he said, ‘Steve, that one’s gone...it’s gonna kill people. You’ve done it again because you have the new on the old.’ Bunny Lee can see the mileage in that. He’s been doing it for years. That’s how it goes. People like Capleton and Anthony B and Sizzla have made their decision. They’re going to put out as much music as they can—10 a week if they can—because they’ve got things to say.

Most people have to punch a card in the West. They become a commuter, this that or the other. But they’ve all got a little ‘thing’ because that’s what keeps them sane. People do drastic things to establish their identity, stupid and silly things to get attention. People in the ex-colonial world get twice as little attention. They are doubly removed and women are trebly removed. It is all about a society that alienates and excludes, and that’s the society we live in. Music gives us a way of overcoming the alienation and saying I do mean something. I am somebody. If only for 2 and a half minutes. I don’t feel inclined to slag people off for jumping on a riddim track and saying some half-remembered Buju pattern or some Ninjaman business or whatever. If it gives them a reason to live, makes them be somebody, that’s what we need. We all need to be somebody. The problem is that the people who are somebodies really are nobodies.

E: And they don’t let anyone else take their turn.

S: Exactly. In a sense there is a certain therapeutic aspect to it. And that’s what music is anyway. I was watching a documentary on

No comments:

Post a Comment