Here's a version of the piece I wrote for the Montreal Mirror this week. I'll try and work up a take with more info--I spoke to Beenie Man for a while, so I gots a lot more stuff, though some of it is somewhat confusing and bizarre.

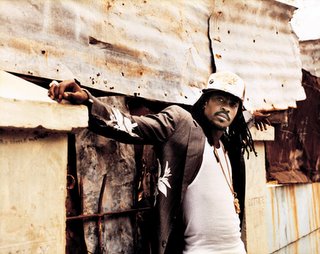

Here's a version of the piece I wrote for the Montreal Mirror this week. I'll try and work up a take with more info--I spoke to Beenie Man for a while, so I gots a lot more stuff, though some of it is somewhat confusing and bizarre.Beenie Man, born Moses Davis, is one of the more controversial and confusing characters in the Jamaican music industry. Demonised internationally for his hateful homophobic attitudes, adored and hailed as a ghetto success story in Jamaica, and embraced by producers, performers, fans and the Grammy awards in America, the one-time “boy wonder” has apologised for his offensive lyrics, but he’s also craftily maintained his stance in yard. Though he’s tough to pin down—and whether a man who refers to himself as a “Grindacologist” can really take a moralistic stance à la Capleton is an open question—there’s no doubt that Beenie Man has cranked out some of the most entertaining and engaging dancehall tunes ever. And thankfully, those, as opposed to the few negative tunes, are what he’s known for. Want proof? Two words: zim zimma. The Mirror caught up with him at his recording studio where he was working on a new album.

M: For your new album are you going to stick with more of a serious dancehall feel like you did with Back To Basics?

BM: Yeah.

M: On Tropical Storm you worked with the Neptunes and Janet Jackson—it was very internationally focused. Do you think that the international audience is ready for dancehall?

BM: The problem is, you have to give it to dem until they ready fi it. Because dem never ready fi rap music either: gangsta rap or all of dem tings dem, until gangsta rap becomes the biggest music in America, seen? So it’s for us to feed dem the dancehall music until dem becomes familiar. It’s not like everyone in America speaking Spanish and look at it: reggaeton is big, yuh know? If dancehall make that music, then dancehall can make it.

M: You’ve been involved in reggae since you were a youth.

BM: Since five.

M: And you’re coming from Waterhouse, a famous area for music in Kingston. I was wondering if you could tell me what the influence of King Jammy’s and the Waterhouse sound was on you.

BM: I was before King Jammy’s. My uncle used to own a sound call “Master Blaster”. It when Jammy was engineer at King Tubby’s studio. Tullo T, Pompidou, John Wayne, all of these artists didn’t really have a chance. From that day now den Jammy’s, pick up di dancehall ting den. Him becomes an international dancehall sound. It was like a highlight of his influence towards the music, but there was good music before Jammy’s sound. Jammy’s give wi a chance to go out there so people can know the product of Waterhouse artists. Wi respect Jammy for that. He never give us no influence or nothing, we influence him fi build a sound. Him live in a government house and him have an 8-track machine, that before him become King Jammy.

M: So you’ve seen the music develop.

BM: Jamaican music start get recognized now, seen? Sean Paul sell five million, Shaggy sell, what, 30 million?

M: And now Damian Marley.

BM: Selling a lot, so you dun know, dancehall is there.

M: But a lot of people see dancehall as being all gal tunes, gun tunes...how do you define dancehall?

BM: Dancehall music is the authenticness of Jamaicans and the militancy of Jamaicans. That’s what it is, because it represent the culture and nothing else, that’s what it is.

M: It allows people to talk about a lot of different things.

BM: Yes, it represent you. Everybody is not politician or writer for newspaper. You express yourself through the paper, I express myself through the music.

M: People have written about your lyrical battles with Bounty Killer and, more recently, your more literal battles with Capleton. Has this conflict been resolved?

BM: That was a long time ago, like three years ago. People still have grievance inna dem heart, but not mi. For mi it’s peace, that’s it.

M: Much like Capleton, you’ve received criticism for your lyrics. In fact, when I reviewed Back to Basics for the Montreal Mirror, I received criticism myself for having reviewed a record by someone who holds homophobic beliefs. How would you defend yourself?

BM: People just try to fight against the music, they’re not only just try to fight against mi, they’re try to fight against the music. I am the king of the dancehall. I am the one that can take the music to the level where it is, I am the one who can represent dancehall music like how Michael Jackson, him represent pop. Dem don’t want mi to reach that level. People ask mi this same question and I tell them that I am against man that have sex with little kids. I cannot be against man that have consensual sex. If two big man want to have sex, it’s their perogative, that’s my opinion. But if you try to get the likkle ghetto youth ‘cause dem nah have no money and dem come with the money and try to give to dem. That is what I am against. I tell that to di world.

M: So your problem is with pedophiles.

BM: Yes. My foundation is the Beenie Man Foundation for Troubled Youth. Some molested kids mi have inna mi foundation wi have fi deal with. We have fi fix dem mentally and physically, fi true.

M: And also, I know that here in Montreal and in Toronto, people are specifically worried about the violence in the music and how it affects young people.

BM: There’s no violence in di music man. Violence in people heart. That’s foolish, no violence in di music. Some write di baddest gun tune inna di world. Why? Because it in di imagination. People need to stop that, talking about violence and music. Music have no to do with violence.

M: Do you think that if people can talk about it in a song they won’t do it in real life?

BM: Simple. Violence is there; it’s a reality. Kids live what dem learn. Man is shot every day for nothing, police kill people, innocent people every day for nothing, That’s what they talk ‘bout.M: What do you think is the solution?

BM: I do community development. Everywhere violence is going on, I try to create a football competition, I try to create a football field, I try to create some work or a clean-up campaign. I try to get dem look at a mirror to see the reality of these tings, because these youth dem a shoot their own friends. So that is what I do. Then every year I keep up a free show, it cost like 3.7 Jamaican dollars to do it, but these people nah make millions of dollars a year. I invite all the top stars in Jamaica and di people who cannot afford to go to the Sting or the SumFest or the SunSplash can just come and enjoy themselves right here.

M: So if you act as selector and were going to drop a few tunes, what would you play for the people? And you can’t choose yourself!

BM: Well it depends on the vibes and di people dem, yuh know? Say you go to a dance and dem play riddims and di vibe it is dead. You try to lift up di crowd by playing dem more popular tune and then go from there. But if you in a dance where di vibes is more conscious so you go with Jah Cure, see mi a say, you try to keep it at a level so you cyaan really pick a tune the way they’re played. It’s a selector ting. You say “if” I am a selector—I’ve never flopped a dance before.