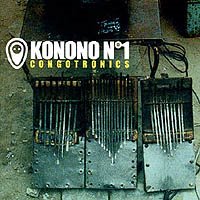

Due to an inability to get through to Blogger while in Ethiopia, here is the long delayed interview, as promised, with Vincent Kenis, producer of the Congotronics series. It an interview that is in the Mirror as a run up to Konono No. 1's performance at the Montreal Jazz Fest. I could only use a tiny bit of the following interview, but I really found Kenis interesting...I'd like to speak to him again sometime.

EM: You initially heard Konono No. 1 on the radio in the late seventies and then went to the Congo to find them in 1989. What drove you to do this?

VK: I already had some experience with modern Congolese music. I had been there in ’71 and stayed one week in Kinshasa. I was really intrigued by popular Congolese music. I heard all sorts of stuff—tradi-modern music. So, in ’79, when I heard this it was like a concentration of everything. At that time I was playing in a New Wave punk band with a lot of emphasis on distortion. I also played a lot with Congolese artists such as Luambo Franco and OK Jazz and Koffi Olomide. So this led me to be sensitive to Congolese music in general. There is, of course, wonderful traditional music.

EM: Is there anything that characterizes Congolese music?

VK: When it became popular in Africa in the sixties it was mainly guitars with echo and delay with very sweet harmonies. And there was a very lively second part when people get on dancing and the horns were more prevalent in the 70s. On top of that, Congo is like a subcontinent. It is huge. Kinshasa is a capital of a huge area of traditional music which is constantly fusing, and this is what makes it so strong and so fascinating, for me.

EM: Band leader Mingiedi has been quoted as saying that he needed to amplify his likembe to compete with city noise. What do you think about this pragmatic need to connect traditional music with technology?

VK: They make music with what they have. And they happen to have that kind of equipment and to circumvent it to get a new sound, a new way of playing the music. In the beginning, you need to find what sounds the best, what sounds the loudest. After a while, they just choose between all the junk they have—what junk sounds better than the rest of the junk. Now they are opening up to new sounds, new possibilities. They never had a proper PA before, and it’s a question of balancing the ugly, dirty sounds they always had with more comfortable sounds. Also, they never had good bass amplification. It’s not like in Jamaica, you don’t have soundsystems that big in the Congo. It’s always a bit tinny, happening in the mid-treble. They discovered sub-bass and have been getting into it, exploiting it. It’s really interesting. The sub-bass element of their music was really suggested while we were pre-mixing the stuff right after the recording sessions. It was quite a novelty, the technology.

EM: As a producer, from the west, going to the Congo, recording music, what are the challenges for you? How do you view your role?

VK: Myself, I have an experience as a Congolese musician, so to speak. I discovered Congolese music through the Cuban side. I have no colonial past, personally. I met Congolese musicians because they played in the same Afro-Cuban bands as I did. So I became friends with a lot of people and people know me in the Congolese music circles as the one white guy who played with Franco. I’m part of the family. I’ve played in Kinshasa with a lot of people. People know me for being that before they know me for being a Belgian. They don’t care if I’m a Belgian or not, as long as I can make them laugh! (laughs)

Of course we discuss and we have our views on politics, but, you know, I’m not the king of Belgium. It’s not a problem.

EM: How important do you think it is to have an understanding of the place, the context in which music is created?

VK: The more music travels, the more it needs to state where it comes from. I’m really excited about internet possibilities, to help join the diaspora from the Congo. That is one of the plans we have, to play music with people from Brazil, Belize, and Cuba. We send them the songs, they send us back overdubs and we decide with the musicians how it is going to be.

People tell me about the DVD that they understand the music so much better after they saw the pictures. It suddenly makes sense, you know? Some sounds, the drums are really complicated, but as soon as you see the dancer dancing to it, you see that it is a very very rigorous and very skillful affair and you just get captivated. You have to show where you come from.

We’re in the process of mixing, for instance Kasai Allstars is a mix of all different groups who had never dreamt of playing together until this Belgian idiot, this naïve guy, said “Why don’t you play together?” They said, “but we don’t have the same scale.” I said, “why don’t you build a scale and transfer the scale of the other guy and I’ll pay for it?” You know, get together and it’s a constant flux of cultural action between these musicians. And this is the way it has always been. They are not really tribalistic in that sense. For example, Swede Swede, which I produced a long time ago was supposed to be a pure group from the Mongo region. But the lokole player, lokole is a really traditional Mongo drum, was from Kasa, a completely different region and he was well accepted. This is in Kinshasa, I don’t know about the rest of the country, except for the south part. But Konono No. 1 are very much into experimentation and new things. And they are senior citizens! They are not into tribalism. But I hope it doesn’t come back with the elections, that’s my fear.

EM: With the positive things about technology, there must also be a negative side?

VK: Of course there is going to be more experimentation, and there is going to be more challenge from that. The founder of Konono No. 1 is 73 years old, he is not going to change a thing. But the rest are open to many new things and technology. Maybe they have never thought of their sound as an object to watch, to compare to others. They see now and are quite conscious of textures of sounds in records they hear [in Europe]. They know that their distortion is unique.

At first, it was a question of prestige. “I am the boss I must have the big amplifier, no matter what it sounds like.” It had nothing to do with an experiment with the music

As soon as you go through this and you say, hey we are making music, lets be comfortable, let’s try this, let’s try that, I think technology just finds its space naturally, The fascination for technology lasts as long as you don’t talk about music. And I’m there to talk music, to propose sounds, to propose solutions. The fact that I have the computer and I can mix all the time with them, the object is in the making and the question is what do I want it to sound like. It is not a question of technology versus tradition. It is just making a musical object that works. And that’s it, and that’s what my ambition is.

EM: Konono No.1 has been around for quite some time and, apparently, is seen as passé. What do you think about new music coming out of the Congo?

VK: I wouldn’t want to describe it, actually. It seems to be quite stagnant at the moment. I must say, I haven’t been around Kinshasa as a talent scout for a very long time. I’ve been just working with people I already know for the last three years. I’ve heard there is a hip hop scene growing. But, the main thing you hear in the streets, for my taste it is terrible, religious music. The new churches are really powerful there. They are the only ones who can afford big PA systems so they are really loud and they play gospel, basically. The last authentically Congolese group, and I use authentic knowing that, in the Congo, it is suspect, its members are at least forty years old, so the younger generation has nothing to refer to, so they take what’s around. So it is gospel music. They get into R&B also, but this is only the rich kids and there are not so many [of them]. Most of the people just play music with what they have. They invent instruments in the backyard and anything goes. It is a very very poor situation in Kinshasa. I’ve been in Bamako, [Mali] it looks like Switzerland to me compared to Congo. Not so many people have access to the outside world and they haven’t been used to look for it. Now they have to because nothing much is happening.

EM: Does the international popularity of the Congotronics series get back to the Congo?

VK: Maybe not now, maybe later. I think the new generation is bound to like this sound very much. Because it is really close to what hip hop or dance music sounds like when you have nothing at all but chairs and brooms and stuff like that to hit on. This music is unique in the world and they are going to incorporate it, I am sure. I hope so, anyway! If not, we’ll make some in my basement in Brussels.